Mary Beard: What’s the point of classics?

Dame Mary Beard is a Professor of Classics at the University of Cambridge, a fellow of Newnham College and Royal Academy of Arts Professor of Ancient Literature. She is also the Classics editor of The Times Literary Supplement and has been described as “Britain’s best-known classicist.” She has lectured at a number of prestigious universities, including Cambridge, King’s and University of California, Berkeley, as well as presenting a number of historical television series.

I want to start, appropriately enough, with some lines from a poem, not by John Donne, but one written centuries later in 1938 by the Irish Oxford poet Louis MacNiece, who for a couple of decades after reading Classics here, was a professional academic classicist teaching Greek first at the University of Birmingham, then at what was Bedford College, London, and finally at Cornell in the United States, before giving it all up for part time poetry and part time BBC writing. MacNiece, was by all accounts enigmatic, slightly aloof, a truly dreadful lecturer and quite, to put it politely, high maintenance. He was described by Antony Blunt, as irredeemably heterosexual, which is not hard to decode. But that’s another story.

The poem that I’m referring to is his long, partly autobiographical Autumn Journal. At the opening of one of its main sections he reflects with some irony on his classical education at school and then at Oxford between the wars. Just to be clear, by classics, he like me, is referring to the combination of Greek and Latin languages, literature, culture, history, philosophy, art and archaeology of the Greco-Roman world. I want to read a couple of passages from this poem, which are a bit like a sermon:

Which things being so, as we said when we studied

The Classics, I ought to be glad

That I studied the Classics at Marlborough and Merton,

Not everyone having had

The privilege of learning a language

That is incontrovertibly dead.

A few lines later, he goes on, ‘the classical student is bred to the purple. His training in syntax is also a training in thought and even in morals; if called to the bar or the barracks he always will do what he ought’. Now elsewhere in the poem, he reflects on his own engagement, not so much with how he was taught the structures of classical education, but with the almost impossibly distant world of ancient Greece itself. Hellas, as he calls it, by its Greek name. Not with its supposed glories, but with the real-life people who often get passed over and sometimes the seedy underbelly of classical culture:

. . . when I should remember the paragons of Hellas,

I think instead

Of the crooks, the adventurers, the opportunists,

The careless athlete, and the fancy-boys,

The hair-splitters, the pedants, the hard-boiled sceptics,

And the Agora and the noise

Of the demagogues and the quacks; and the women pouring

Libations over graves

And the trimmers at Delphi and the dummies at Sparta and lastly,

I think of the slaves.

And how one can imagine oneself among them

I do not know;

It was all so unimaginably different

And all so long ago.

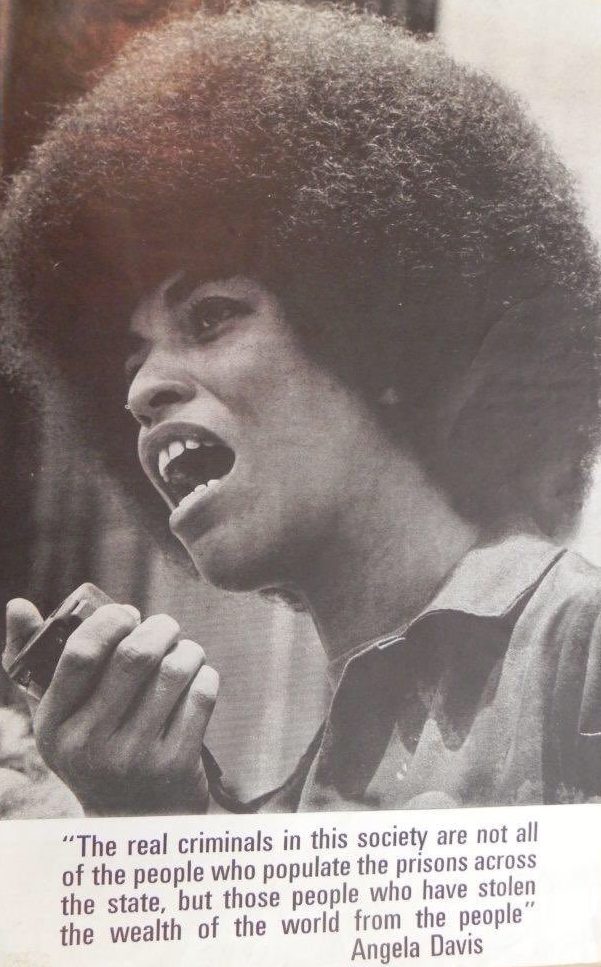

I first read that in the very early 70s when I was 15 or 16, and it opened my eyes to a very different way of looking at the Latin and Greek that I was then studying at a very good, very traditional girls’ High School. I think like many nerdy teenagers, I lived a strangely split existence. I was a would-be free-thinking revolutionary in my head, but day to day at school I was a decidedly unrevolutionary swat learning my Latin grammar with sickening obedience and being rather too committed to getting ten out of ten for my translations. When I think about it now, I seemed like almost a horrible combination of a goody two shoes and Rosa Luxemburg rolled into one with rather more shoes than Luxemburg. I still remember how I used to do my homework on the kitchen table at home, above which I persuaded my parents to let me pin a poster of the then imprisoned black power leader Angela Davis, beneath whose profile I would struggle diligently with my Thucydides and my irregular verbs. Thanks to the amazing magic of Google images, I managed to come face to face again with the very poster.

Into this split teenaged existence came Louis MacNiece’s poem, pointing to the connections between politics in the broadest sense and the subjects that I myself was then learning. Although I might have seen myself as a young revolutionary, I had never thought before about the social and cultural capital that had traditionally gone with the study of the Latin and Greek that I was enjoying and was quite good at. I’d never thought about the role of classics as ‘a gatekeeper of the British social and political elite.’ It took me some time back then to realise that MacNiece’s phrase ‘called to the bar’ was a reference to a legal career rather than being invited to the pub. Nor had I consciously reflected on the loaded uses to which classics had sometimes been put; from upholding conservative styles of art to justifying empire. If I’d spotted that the big bank branches in my hometown tended to have classical columns on their facades, I think I’d probably put that down to aesthetic choice rather than any connection between the authority of money, capitalism and the politically symbolic repertoire of classics.

Equally important, were MacNiece’s prompts to look a bit harder at what modern students or scholars were expected to notice in the ancient world itself. Up until then, I had generally accepted a kind of diet in classics of great men, Caesars and a few genocidal generals, possibly with a sprinkling of women behind the throne. Now I don’t think that MacNiece was much of a feminist, in fact, you may have spotted that I passed over it rather quickly; how his verses assume that all classicists were male, ‘his training in syntax’, he wrote. However, at the particular moment that I read it, it was this poem more than anything else that prompted me to realise that there were bits of the ancient world and its inhabitants that I had not been taught to see. Or perhaps that I had been taught not to see. The ordinary, the crooks, the fancy boys, as he put it, the women, the slaves, and, of course, the people that my Angela Davis poster was talking about. MacNiece’s message has stood by me for decades. Look, he seems to be saying, for what you can’t see in the ancient world and always try to tell the story from the other point of view.

Why were enslaved people in antiquity always represented small? This is an ordinary wall painting from Pompei. It’s easy to spot the slaves because they’re little. Where were the people of colour? How can you capture the perspective of the conquered, or the women, the factory workers, the poor and well, the hopes and the fears and the aspirations of ordinary regular people like us. To push MacNiece further than he went; How do you read the stories of violence and misogyny that seem embedded in ancient literature and continue to be part of our own representational world, even now?

Some of you will know that one of my favourite, but particularly unpleasant, recent versions in which the ancient decapitation of the mythical snakey Gorgon Medusa is reworked to end up as the image of the severed head of Hillary Clinton. This is from a U.S. presidential campaign tea mug. You could also get it on tote bags, on t-shirts, on mouse mats, and wherever you wanted. This image of decapitation, which goes back to the ancient world. I doubt that many of the people who bought this knew the story of Medusa in any detail, but they damn well knew what it was about.

Now, it’s 50 years on from my first encounter with Autumn Journal, and I’m really pleased to say that it helped me work out my own slightly different engagement with the classical world and the way we study it, which I have gradually come to feel reasonably at ease with. I feel much bolder than I used to in resisting the temptation to claim that the Greeks and Romans are relevant to us in any narrow sense. Still less, that they provide helpful analogues for modern politics.

The most frequent query I now receive from journalists is: what Roman emperor do I think that Donald Trump is most like? When I get this, as I frequently do, I take pleasure in explaining that while that might be a fun party game, historically, any superficial similarity between a modern U.S. president and an ancient Roman emperor is practically meaningless. That usually takes quite a lot of time to explain. If I don’t have time to go through all that, I tend to suggest a Roman Emperor that they wouldn’t have heard of and take some comfort that at least they’ll learn something by going away and looking him up. I should say that the second common question is: did immigration cause the fall of the Roman Empire? To this, the answer, at least when the question is put like that, is emphatically no. But beyond that, I think I now feel fine in a way that I wouldn’t have, about not admiring the Greeks and the Romans in any straightforward way. People often say, “Mary Beard really loves the Romans”. I wouldn’t say “no, she damn well doesn’t,” but she certainly doesn’t want to go back there unless it’s a first-class return ticket!

What I feel is something quite different from admiration about these people. It’s quite simply, that some of the things that the Greeks and Romans wrote and made and left behind them, from great literature to apparently trivial bits of papyrus, are still worthwhile reading, reflecting on, engaging with and thinking very hard about. At the highest level that goes from their dissections of imperialism and corruption, because we have to remember, uncomfortable as it is, that imperialists themselves are often the most acute analysts of the faults of empire, to the challenges of any straightforward version of patriotism that are set to us by poems like Virgil’s Aeneid. Although Classicists, who I think can be miserable at times, often lament that so much of classical literature has been lost, let me just remind you that we still have more stuff written in Latin and Greek, than anybody but a prodigy with no social life could possibly get through in a whole career. I think often one should be more surprised by that claim but that claim than we often are.

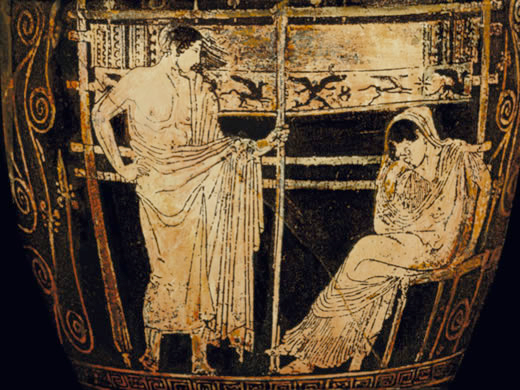

I have no doubt too that in interrogating the dialogue between classical culture and modernity, that’s been going on for hundreds of years, we do begin to understand better why Western culture operates like it does. Whether that is written about the silencing of the public voice of women. Here is a wonderful Athenian pot depicting Odysseus’ wife Penelope and her teenage son Telemachus, which for me evokes that moment early in Homer’s Odyssey, the second work of European literature to survive, when Telemachus becomes the first bloke in European literature and in European history to tell his mother to be quiet.

‘Speech is man’s business,’ this little squit says to his mother. Or whether with the king of crucial debates about the rights and obligations of citizenship, the Latin phrase civis romanus sum– I am a Roman Citizen, was famously refused by Lord Palmerston in 1850 and then adapted by John F. Kennedy in Berlin in 1963 as a slogan to capture the protection offered by modern citizenship.

It goes back to the works of Cicero in the first century B.C., though I strongly suspect that neither Palmerston nor Kennedy realized that in the Ciceroen original, it was a phrase that had been cried out fruitlessly by a Roman citizen who was being illegally crucified, to get attention which not forthcoming, he repeated ‘I’m a Roman citizen who should not be crucified’.

I think of either Palmerston or Kennedy had realised that they might both have thought rather harder about the problems and ambivalences of citizenship now. I think he would have given a rather different spin to Kennedy’s Ich bin ein Berliner speech. I have no hesitation, in other words, in saying that keeping classic’s in the picture hugely enriches our understanding of Western social, political and cultural structures. They often thaw our assumptions on which those structures were and all based. In saying that, I am not saying that I think Western civilization is solely a product of the classical tradition, it is much more varied than that. It would be truly ghastly to be living in a hand-me-down classical world. I’m not saying that classical or to literature are superior to that of other traditions. For a start, I’m not remotely qualified to make any such judgment, and anyway I don’t think hierarchies of that kind mean anything; superior at what? To whom? The same goes for Western civilization itself, which I’m not singling out for its pre-eminence over other civilizations. But because I don’t want to hype my claims by implying that the Greco-Roman classics have the same degree of purchase across the whole planet. They don’t. Don’t let’s pretend that they do. For me, it’s enough that a lot of people, wherever they are, still want to read Tacitus and Plato. They still want to visit museums and work with, adapt and reformulate the Greco-Roman artistic tradition. I’m told that Plato is still the best-selling philosopher in the world ever.

I also have an increasing sense of the value of classics in giving us new perspectives on ourselves and at prodding our uncertainties and some other sanctimonious self- righteousness that can afflict modernity, even if we sometimes need to work harder at that that we sometimes do. That came home to me most powerfully almost 20 years ago when I was in the Coliseum, at Rome, with time on my hands. So, I decided to eavesdrop on what the school parties were being told in the Coliseum as they were shown around. They were from lots of different countries, but the script was almost always the same. The teacher or the guide would start by asking the kids what happened here, and some eager child would put his hand up, and it usually was a boy, and would say words to the effect of ‘they used to kill people here for pleasure and throw them to the wild beasts’. The teacher would then almost always respond, ‘would we do that now?’, and the chorus came back in harmony; ‘no, miss’, and a kind of awful, self-satisfied glow of confidence in human progress would descend on the whole bloody lot of them.

I think if I witnessed that today when I was braver, I’d probably interrupt and I’d say, hang on, when do we see cruelty for pleasure in our own culture. Who’s still getting a thrill out of gladiatorial combat? Which of you have bought a gladiator model and who has just had their picture taken outside the Colosseum with some scam gladiators for a rip-off price? And anyway, who’s queued up to see the movie? You can go on and on. I think if it was today, I might have added: and how do you compare what went on here with the fact that millions of people have recently watched footage of a real-life mass-murder on their smartphones? My point is not to make some stupid claim that gladiatorial slaughter was not as bad as we think it is, but to insist that if you seize the opportunity, you find that our dialogue with the ancients can turn back on us. It can make us sort of anthropologists of ourselves. Now, in some ways, I think that’s probably true of any study of the past or any elsewhere, but the particular combination of familiarity and difference embedded in the classical world makes for a particularly powerful light shined not on men only, but on us. Hold it in your mind while we move back to MacNeice, from where we’ve strayed a bit, and to his political reflections on his experience, not of the ancient world itself, but of classics, especially the Greek and Latin languages, as a subject studied institutionally at schools and universities.

What MacNiece is doing is characterizing classics as, in his experience, a mechanism of exclusivity. His argument goes, and happily, this is no longer entirely true, but his argument goes: only the rich learn Latin and Greek, and it’s their knowledge of those languages that by a kind of conservative feedback loop legitimates their position as the rich elite and so underpins the traditional conservative social and cultural order, in a haze of moral superiority that the sheer uselessness of the subject both inculcates and mystifies, while at the same time as a gatekeeper of privilege classics offers a practical route to power, to the purple, as MacNiece puts it using Roman terminology, singling out the law and the only hint of British imperial administration lurking behind. That summary is obviously far less elegant than MacNeice’s elusive verses. But in those terms, it represents a position that is familiar to us from, for a start, media discussions of learning dead languages. It’s familiar to me and to some of my colleagues in the profession. It’s a familiar line which is now taken by some fairly strong voices within the academic profession of classics itself, who feel that the toxic, conservative, discriminatory, past and possibly present, of classics as a discipline is so toxic that unless the subject completely reforms itself, it will be better off destroyed. Now, whatever you think of that position, if you’re addressing the question of the point of classics now and I mean classics as an academic discipline of study, you can’t avoid thinking about that so-called toxicity, it’s elitism and its discriminatory aspects.

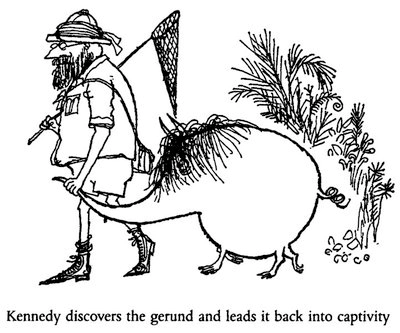

This cartoon sums up the position in a rather more light-hearted way. It comes from the series of 1950s and 1960s books for kids with the antihero Nigel Molesworth, a lad who resolutely refuses to be moulded into elite shape, even though he is force fed Latin at his terribly third-rate public school, St. Custards. In it, we see Benjamin Paul Kennedy, the author of the most famous Latin grammar book of the 19th century, which was actually ghost-written by his daughters. He’s dressed here as an imperial style explorer, capturing that trickiest bit of Latin grammar, the gerund, here reimagined as an exotic animal and as the caption says, ‘leading the gerund back into captivity’. It’s the perfect triangulation of imperialism, the Latin language, and because although Molesworth was a rebel, he was still a toff, class.

It goes without saying that in some ways classics has been, and some would say in respects still is guilty as charged, a knowledge of Greek and Latin really used to be the gatekeeper of elite privilege. It was not until 1960 that Latin ceased to be an entry requirement for Oxford and Cambridge, and it was only after the First World War that the compulsory Greek requirement was abolished, following huge arguments both in Oxford and in Cambridge that it stretched over decades. They partly came down to the appalling brute fact that the young posh boys just learned the translation of their set texts off by heart, and so it wasn’t a test of Greek at all, but of expensive, privileged rote learning. It was doing no intellectual good whatsoever. I looked at a few papers from these exams a few weeks ago, and they say in the instructions to candidates to keep as close to the translation as you can. They ask them to translate the Greek New Testament, and they say that the candidate is advised to stick close to the authorized version. Well, that means they read the authorized version, learnt it and spotted the passage. So, you can see why the radicals at Oxford and Cambridge thought this was a totally worthless. You got that kind of sense of the British elite the past using classic’s as an entry mechanism.

You might also argue that class privilege was actually written into the name of the subject itself because there is an undeniable etymological link between classics and class. The term classics comes from a second century A.D. Roman antiquarian called Aulus Gellius who adapted a term that had long in Rome been used to describe the formal hierarchies of Roman wealth and status: social, economic, or whatever. He took that literal class vocabulary to denote also the best or the classiest kind of literature. Classics, in other words, has not just been defined as posh, the very word classics originally meant posh. Now it’s for that reason that some of my colleagues now would like to change the title of the subject entirely to call it Ancient World Studies or whatever. I’ve always felt rather laid back about this. Most people in the world in the world have never heard of all Aulus Gellius and when I tell people on trains that I’m studying classics, I always find it quite a relief that they think that I work on Jane Austen and Charles Dickens and things like that. It makes for generally a better train journeys, so I’m happy with classics.

But leaving aside the name of the subject, there’s no doubt that, classics, particularly languages at school and university, still carry around some of that burden of elitism. Now, thanks to a huge amount of work done by colleagues, who are busting a gut to get Latin and Greek and ancient civilization firmly embedded in the school curriculum and made available to all. This is changing, but there’s still a lot more to do. I’m going to let my prejudices show here. Every time some parliamentary fop opens his mouth and spouts Latin, that de-poshification project take several steps backwards. It’s not just about elite gatekeeping, but it’s also about the authoritarian, militaristic and far-right causes that have found legitimation in the study of the ancient world and which somehow the subject can sometimes seem to be complicit. Benito Mussolini in Italy conscripted the images of Roman emperors to his fascist movement, and he cleverly deployed, as you can see here with the Colosseum in the background, the monuments of ancient Rome as backdrops to his own ceremonial extravaganzas.

He also paid for the excavation of many of the ancient Roman monuments that we as tourists now flock to the Altare della Patria, the Circus Maximus and much more. You can’t just write Mussolini out of the history of ancient Rome. He has provided the ancient Rome that we now see. And it’s also certainly true that the British Empire did on occasion look back to the Roman Empire as its legitimating predecessor. And modern far right groups have invested heavily in what they see as a powerful Western and white classical tradition. I’m going a lot further to the right than Jacob Rees-Mogg to a number of openly white supremacist movements who often parade highly inaccurate versions of their classical ancestors. But to move to a European group, here are two posters that I found on the web whose message is pretty plain. The culture of Europe identity: Europa is classical, and white.

It will perhaps come as no surprise that the people who put out this kind of propaganda are a very resistant to the fact that much, if not most, of ancient marbles culture was not originally white at all, but brightly painted in colours, all sorts. They’re so resistant that they recently threatened death to one young American scholar who had fairly simply laid out the clear arguments for classical sculpture being painted. And it was no doubt some of the same guys who smothered me with abuse online for saying that this image was a not implausible image of an elite Roman family, in Roman Britain, there being good evidence for the presence of people of colour in the province of Great Britain. That was very hard for quite a lot of these guys to take. In fact, I think our recent bio archaeology in Roman Britain is an extremely powerful antidote to the not uncommon fantasy that no black person ever came here to the 1950s. There’s quite a lot of really old evidence now.

As a classicist, how do you counter that? How do you respond to that version of the subject’s toxic history? Well, one simple way is to point out that this is only one side of the story. It’s true that the classical tradition and classical scholarship itself has been linked to some very nasty things and that we don’t always really realize exactly quite how it’s been linked. It comes as a shock, to many people to discover that one of the best in inverted commas and still the most popular books on Roman Everyday Life, which is Jérôme Carcopino’s Daily Life in Ancient Rome, was written by a paid-up fascist, the Minister of Education in Vichy France, who excluded all Jews from French academies. And when you know that is what he was and you read his everyday life, it doesn’t half jump out at you. But he’s still blithely being read as if it’s political past meant nothing.

But the checklist on the other side of this argument is just as striking. Ask people what subject Karl Marx’s doctoral dissertation was on? Well, Greek philosophy! What underpins Freudian psychoanalysis? Greek myth. The 1832 Great Reform Act, which vastly extended the franchise in England and Wales, was partly driven by historians of Athenian democracy such as George Grote, who saw in Athenian democracy a model for what you could do here. As a project about classics and class directed by Edith Hall in London has shown, there is also a radical working-class tradition of conscripting classical symbols to working class causes. Here is a nice Hercules strangling a snake, presiding over a plea for the end of destitution, prostitution and exploitation.

British Trade Union movements in general looked back to the plebeians struggles in the early Roman Republic in the fifth century B.C. as a model, for example, for their own withdrawal of labour. Rome, in other words, for them, legitimated the concept of a strike. Now, obviously, you can’t do a scorecard here. You can’t check out the good versus bad uses of classics, even supposing we could agree what the good and the bad were. But it is a reminder that classics, despite what you sometimes hear, does not intrinsically have a politics. I don’t think that any academic subject, with the possible exception of women’s studies, does have a politics. It may, as MacNiece nicely explores, become politicised. It can be used politically, and we need to attend to those uses, but it does not of itself intrinsically have its own politics. That point, I think, significantly complexifies the idea of just how toxic classics has been. It’s a complex story that I want to push a bit further. In exploring the relationship of classics to the British Empire, a relationship which has been frankly over mythologised. I think classicists are extremely good at studying Greek myth, but they’re not always so good at studying the myths that they propagate of their own subject.

Part of the strength of classics, I’m going to hint, lies and lay in its own ambivalences about itself and its role about exactly what it’s for and what it is. The blokey self confidence that MacNiece picked up certainly exists, but it’s always been balanced by a sense of fragility about what this subject was all about and what its place should be. It’s worth remembering if you want just a single illustration of that, that 120 or so years ago, what we would have thought the high watermark of classical dominance in the education system of this country, the gents of Oxford and Cambridge in London were getting together to found the National Classical Association, which still exists. Why were they doing that? Because they thought the subject was in imminent danger of extinction unless they launched a crusading organisation to protect and preserve it. There is something, I think, an embedded nostalgia in classics, that every generation of people who study the ancient world always believe that A) it’s going down the tubes and B) their predecessors did it better. Neither of those claims are true.

Once again, it would be absolutely wrong to deny that there were close connections between British imperialism and the Roman predecessor, or between 19th century constructions of its right-wing predecessor, because there’s always a circularity here, as nineteenth century scholars and politicians both took the Roman Empire as their model, and they reinvented Rome in order to fit their own picture of what they were doing. It’s not as simple as it seems. It went far beyond things that we’re familiar with; representing the British Imperial Mission as if it was Roman, representing themselves, is two nice examples from the Foreign Office, representing themselves as Roman soldiers or comparing British failures in the Boer War to the disastrous Athenian expedition to Sicily in the 5th century B.C. It went beyond that! For Benjamin Jowett of Balliol, it was pre-eminently those who were trained as classicists, and preferably at Oxford, who were uniquely equipped to govern the empire. It was another version of the triangulation between classical education, class and empire that we saw in the Molesworth cartoon and Jowett banged on about it at every possible opportunity.

Yet that summary, true as it is, obscures the complexities of the interrelationships here. For a start, the British and Roman empires made a very awkward fit. History put them on different sides. That is symbolically hammered home by this most famous, in-your-face monument to the British Empire in all of London: The statue of Boudica on the Thames embankment. Boudica, the rebel against the Romans, who has an inscription underneath her, taken from Cowper’s earlier poem, chillingly proclaiming that her descendants would rule more territory than the Romans ever had.

“Regions Caesar never knew/ Thy posterity shall sway”

It seems to me it was a very good encapsulation of the awkwardness of fit between us and the Romans. Here we’re envisaging ourselves as British rebels against Rome. What’s more, the idea that classicists were ideal rulers of an empire was actually a highly contested one. Sometimes, in truth, what was euphemistically named the Indian Civil Service, which as people said at the time was neither India nor civil nor service. Sometimes entry into the Indian civil service was dominated by those who had studied classics, particularly here. Sometimes the rules for entry to the Indian civil service were actually framed in order to exclude Oxford classicists. When Jowett said about Classicists, the only people who had studied Latin and Greek, being the only people who were suited for the governance of the Empire, he was not, as we sometimes naively take it, stating the bleeding obvious. He was tendentiously responding to those who thought the exact opposite. That the last people he wanted to send out to India was a of people who’d studied philosophy. The irony is, although it’s much less well known, that while Jowett and one part of Oxford was busy trying to recruit Oxford classicists to serve the empire, C.P. Scott, who himself studied classics and went on to be editor of The Manchester Guardian, the most powerful anti-imperial paper in the country, was trying to hoover up classicists to get them to use their classical training to denounce the empire. He wanted those who knew their second century Roman historian Tacitus, who, in referring to the behaviour of the Romans in the province of Britain, coined the best description of imperialism ever: ‘They make a desert and they call it peace’. Something that we’re still doing on doing, I might say.

So, there is a debate going on here is not a simple, taken for granted, well known truth that empire and classics go together. My basic point is that in our hunt for toxicity, we miss the fragilities and the ambivalences and the other side of this subject. We hear those awful blustering of Jowett, but we don’t stop to think why he was shouting so loud. An unconventional view as I think it would be, I would locate the strength, and in some ways part of the point and the longevity of classics, is precisely in its uncertainties, its anxieties and its very well-developed skills in self-flagellation and self-criticism. MacNiece, in making his criticisms, was writing as a professional classicist. Some of those areas of fragility remain fairly consistent. What do we study in the ancient world for? Who do we open this subject to? On what terms? But the contours also change. MacNiece in 1938 would probably not recognize the area that has rightly come to the top of our list of anxieties the lack of ethnic diversity within the subject. I know of no one in classics or I think in Oxford actually, who is not keenly aware of that not only with relation to moths and greats, but also in relation to many other subjects. I know of nobody in classics who is not aware of it and is also not committed to diversifying it both in the interests of fairness and in the interests of a subject that is a better subject, and more enjoyable. It’s one of God’s better traits that the more fair an institution is, the more fun it is to be in and the more interesting it is to be in. The idea of diversity is not simply about fairness, it’s about a better subject for everybody. And that’s easy to say, but the question is how? And the answer to how takes me back finally one of the topics that I’ve already touched on.

One answer people say to how you make a subject that looks more representative of Britain now than classics does, is to say we should expand the territorial range of classic’s away from just northern European lands and the shores of the Mediterranean to include Africa and further east on the grounds that making the subject of study look less white European would be more attractive to those who were not a white European inheritance.

Now I think there might be very good reasons for extending the territorial area that classic’s covers. What people call the Greco-Roman world and Greco-Roman subjects, has got pretty fuzzy boundaries. They’ve expanded and contracted over time. No one has ever quite agreed whether Egypt was for Egyptologists or whether Roman Egypt was for classicists and so forth. And there are some expansions, as Joe Quinn recently pointed out that to me are no brainers. I, for one, am extremely pleased that we no longer teach our students about the Greco Persian wars in the fifth century. B.C. expecting them to know nothing about Persia at all, as if we were to teach the origins of the Second World War without only looking at England.

But I worry that in that kind of logic that we’re falling into a trap that is set by the half-baked ill-informed tirades of the alt-right who claim to see their white selves reflected in the Greco-Roman world. You don’t escape a trap simply by deciding to hold up the mirror to somebody else. You might think that the mirror needs to be reformed. Now, this hit home a few months ago when there was another typical storm on social media about the BBC choice of a black actor to play Achilles in their I have to say, not very good drama, about the Trojan War. How can you steal our Achilles? Was the message of many complaints. For me, there was an obvious bottom line answer to this: Achilles didn’t exist, so really no one could hope to play him! My colleague Tim Whitmarsh wrote a blog essay that pushed those points in a more sophisticated direction. It looked at how ancients saw, described and signified colour. He insisted that ancient and modern colour does not match, and that you could not map it onto each other. You can’t take a colour description of Zeus’ hair and say he can’t be blonde. There is no match between those two. The whole point about Achilles was that whatever his non-existent skin colour was, and I say non-existent because he’s actually as fictional as Paddington Bear, he was outside those categories and those significances that we assume to be natural that Achilles is alien. He is strange. He is different from what we take to be the basic coordinates of our world. And that is his point.

What I’m saying is that it is a false promise to suggest that anybody at all can find themselves in the ancient world. That’s just one reason why the alt-right are wrong. For me, what it tells us is that if we want as we must, to diversify the subject, insist even more firmly than we do, that despite the counterclaims, nobody owns classics, however you define it. No one’s identities can be found in the ancient world. This is not a place for identity politics. The classical world is a mirror to nobody. To put that more positively, one of the greatest and mind changing intellectual rewards of studying the classical world is this it is simultaneously familiar because it is in some way embedded in modern discursive practices, and simultaneously so strange. But it turns us into analysts and anthropologists, not only of it, but of ourselves. Classics in a kind of slogany way, is always about all of us and about none of us. That is why it can have and must have diverse appeal and why we can learn from it, as I would like to have said to little kids in the Coliseum or to return to the text of my sermon, as MacNiece put it, ‘it was all so unimaginably different and all so long ago’ and that’s it’s point.